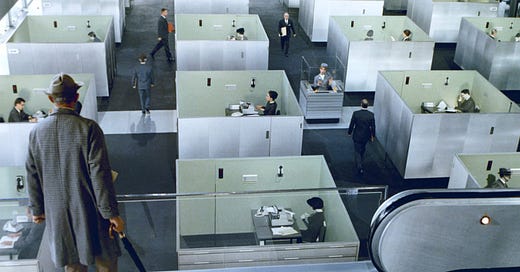

Buildings onscreen

Observations on the two vibiest pieces of architectural entertainment in our times

I am famously behind the zeitgeist when it comes to mainlining movies and television, so forgive me if this feels like yesterday’s news. (In the case of The Brutalist, literally yesterday.) But I was chatting with my pal Eric Petschek, one of the sharpest-eyed, hardest-working photographers today, on the topic of the former Bell Labs in New Jersey and w…

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Ground Condition to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.